Drama,

Poems,

Essays |

A REQUIEM

FOR AYN RAND?

|

|

[Readers will notice some connection between this essay and my piece "Re-Evaluating Ayn Rand". I suggest you read this one first, then the other. I anticipate eventually merging the two.]

It is much easier to point out the faults and errors in the work of a great mind than to give a distinct and full exposition of its value.

Schopenhauer, Criticism of the Kantian Philosophy

|

As I write this, it is the middle of the year 2000, the very last year of the 20th century. At such times one thinks nostalgically about the past, remembering (and regretting) one's past mistakes. Therefore I confess:

--For most of the 1960s and part of the 1970s . . . I worshipped and idolized the Russian-American novelist-philosopher Ayn (rhymes with "mine") Rand.

Don't look at me so strangely! It's not as if I were the only one. Rand had many followers.

Still, she has been dead now for more than eighteen years. (She died at age 77 in March, 1982.) In her lifetime Rand was reasonably well-known, and, among those who knew of her, controversial.

Her literary fate has been unusual so far.

For many writers, their death triggers a period in which their works are more thoughtfully reappraised and reassessed. Critics, now more free of daily partisan pressures, evaluate the author's work, and try to arrive at some final estimate of the value of the author.

Yet here we are. Eighteen years after her death, Rand's ranking among the novelists and the philosophers of the 20th century remains almost completely unresolved.

On one hand, it seems almost Politically Incorrect among some people to even mention Rand in the context of either literature or philosophy, let alone to take her seriously. For example, just a few weeks ago I read a Web critic dismissing her works as "having nothing to do with literature."

Oh, really?

Must we at last now sing a requiem for Rand's influence? . . . Must we condemn her to well-deserved literary and philosophical obscurity? . . . Or should we sing instead Rand's triumphant paean -- an anthem of hope -- and lay her with full honours in our Pantheon, and lift her reputation into the canon of great writers and thinkers?

Well, friends . . . I just do not know.

I know what I currently think of Rand and her work, but I am not absolutely sure how the matter of her future reputation will be resolved.

# # #

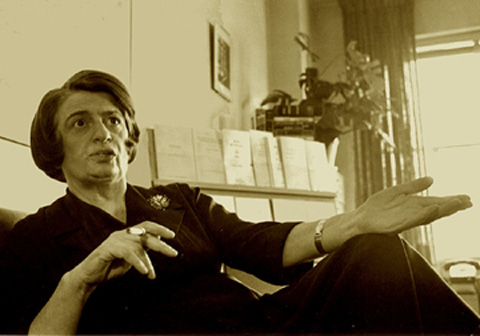

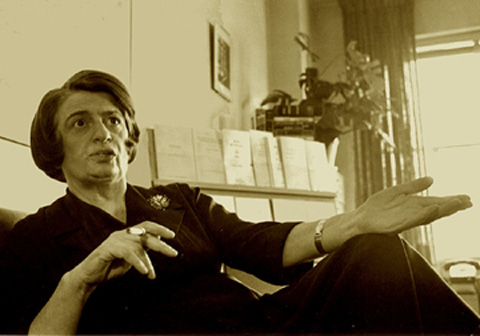

To some familiar with her work, Rand (photo below) remains merely

- a loopy, turgid, didactic and utterly humorless woman's novelist;

- a dogmatic writer of anti-socialist diatribes and implausible fantasies;

- an eccentric conservative cult leader whose so-called "ideas" were not original to her, and have been shunned for at least a hundred years by all sensible and decent people.

|

Yet, strangely, at the same time -- for a growing number of others -- Rand is

- the master thinker of the 20th century;

- the most brilliant novelist of ideas in the history of the novel;

- a genius of the highest brilliance;

- and the spiritual heir -- oddly enough -- to both the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.) and the French poet and novelist Victor Hugo (1802-1885).

And these people see her as a most respectable challenger of nearly 2400 years of inaccurate philosophy.

|

|

| Ayn Rand in maturity |

In fact, some of Rand's appreciators think her almost as important in the history of philosophy and literature as she thought she was.

Enough jokes. Which side is right?

Well, I maintain the appreciators are most nearly right. But my main purpose today is not to evaluate her philosophy but to comment on the growing posthumous influence of this powerful thinker, an influence which, I think, few are tracking.

For it seems to me obvious that year by year her ideas are slipping, without controversy or acknowledgment, into the cultural and popular mainstream.

What is the evidence?

|

- A U.S. postage stamp (at left) was issued in 1999 with her idealized Art Deco portrait; it was designed by Nicholas Gaetano, the cover illustrator of several of her books.

- Several institutes dedicated to her philosophy (some critical, some un-) have recently arisen.

- More and more volumes of her previously uncollected writings (including the recent Journals of Ayn Rand, Letters of Ayn Rand, and Marginalia of Ayn Rand) continue to be published.

- New books and memoirs about her and her philosophy continue to be published.

- More and more sympathetic newspaper articles about her are being published, e.g., that in Canada's influential conservative newspaper The National Post, January 8, 2000.

- A play about her starring American actress Anne Bancroft was produced in London in 1998.

- And a film of her life starring British actress Helen Mirren was shown on U.S. cable in 1999.

|

Surely the postage stamp and the made-for-cable movie indicate that Rand has become as historically respectable as, say, American aviator Amelia Earhart (1897-1937) or American photographer Margaret Bourke-White (1906-1971), two women about whom documentaries and movies have been made.

Yet as a thinker Rand began entirely outside the mainstream. In 1926 she was a penniless Jewish immigrant to the United States, who lied to get in. She toiled for years in the lower echelons of Hollywood screenwriting. Her first novel was a flop. When she finally put together her philosophy of Objectivism, it adamantly, vehemently opposed nearly all contemporary trends in philosophy and literature. Against the contemporary advocates of subjectivism, irrationality, selflessness, naturalism, and big government (I'm putting this in Rand's terms), Rand advocated

- objective reality

- reason

- selfishness

- a heroic view of life

- romanticism in art

- atheism

- and extremely limited government.

Yet despite intermittent ferocious intellectual opposition, her ideas (and friends) no longer seem like outsiders.

What is the proof?

- One of Rand's closest former friends and students, Alan Greenspan, has been since 1987 the highly respected chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board.

- Her ex-disciple and one-time intellectual heir, Nathaniel Branden (see photo at right), is an influential, admired psychotherapist and an important leader of the substantial California self-esteem movement in psychology.

- Her official intellectual heir, the controversial Dr. Leonard Peikoff, had until recently a radio show on which to sound off about cultural affairs.

- Among those who have been influenced profoundly by her are the presidents of numerous Silicon Valley computer companies, not to mention those behind the Electronic Frontier Foundation movement for freedom of expression on the Internet.

- And interpenetration has so strongly occurred between the ideas of Rand's movement and those of the very active U.S. neo-conservative movement that it is difficult to remember who originated and who popularized the ideas both groups believe.

Rand's ideas are maintained by a stable underground of loyal Objectivist followers. They are shared by a steadily growing number of respectable economic neo-conservatives. Having achieved so much success, they can no longer be considered outlandish. True, Christians -- fundamentalist and liberal -- who have heard of her usually remain opposed. And her ideas (and the whole Western world) now confront a challenge from Islam, the world's fastest-growing major authoritarian religion. And many philosophers in academe still ignore Rand's existence, dismiss her ideas, and refuse to debate them. And many other academics perhaps discuss her ideas only reluctantly . . .

Nevertheless, Rand's popularity and respectability continue quietly to grow. Her novels and non-fiction works continue to be reprinted and to sell in reasonable numbers -- about 300,000 copies a year in total -- despite her bad critical reputation as a novelist and philosopher and her influence's being well past its prime.

Or . . . is that influence . . . past its prime?

To me, Rand's cultural influence seems not to be as pervasive on college campuses as in the 1960s, but there is considerable evidence that, at a slightly lower level, it may yet have a long future.

- Since Rand's death, fanatic opposition to her ideas in the press has gradually waned.

- Rand seems to have achieved -- though not total respectability -- at least the attention of the best intellectuals of our society.

Even in the 1960s there was always a small group of young philosophers who were influenced by her ideas (I think of John Hospers and George H. Smith). But especially in the last two years I have sensed an undercurrent of respectable philosophers and thinkers who are willing to reconsider at least some of her thought. Her original body of followers, the devotees of the 1960s, remain about the same in number as when her cult influence was at its height. True, they are more passive now, and divided into squabbling sects. But these older followers have been joined by a steady, dribbling accumulation of others. If Rand remains underneath a cultural shadow, it seems to be a shadow of unfashionability, not frantic opposition. Intellectuals seem no longer to dismiss Rand and her ideas with utter contempt as they did in the liberal 1960s.

For example, in such up-to-the-date encyclopedias as Encylopedia Britannica and the Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia, Rand's ideas receive brief but respectful treatment.

So if her ideas and her friends are being taken seriously, what forces continue to hold her influence back?

- It can be argued that Rand's ideas were unoriginal and out of date.

- It is unlikely that many philosophers have read her most important philosophical work, An Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology.

- Some thinkers argue that Rand's metaphysics (like all metaphysics) has been made obsolete by developments in contemporary philosophy (see my essay).

- Such thinkers argue that her logic is no advance on Aristotle's, while many important developments have occurred in logic in 2000 years.

- They further argue that Rand's ethic of egoism was better defended by 19th-century philosophers such as the Germans Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) and Max Stirner (1806-1856).

- They argue that Rand's ethics of egoism is morally abhorrent and socially impractical.

- They argue that her view of capitalism is naive and social darwinist, like that of the English philosopher Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), and monstrously callous to the poor.

- They argue that the laissez-faire capitalist society she advocated would crush the poor, and divide society into plutocrats and paupers.

- And they argue that Rand was no innovator but simply a radical conservative, the kind of popular so-called "thinker" liberals have learned not to take seriously; in their opinion, history shows that most such conservatives are bigoted reactionaries -- fascists, racists, and plutocrats -- with nothing to offer in the way of logical thought.

All these arguments have been made to dismiss Rand and her thought. But this congeries of arguments seems to have faded somewhat with time. With the passage of several decades Rand's ideas (including their deep flaws) no longer seem threatening (or, perhaps more accurately, as threatening) to liberal or conservative values. True, there is little dialogue between the old admirers of her philosophy (often called "students of Objectivism" or "libertarians") and the philosophy's old detractors, the leftist liberals of the universities and newspapers (and, to a significant extent -- for religious reasons -- American conservatives). Her aging followers long ago divided into quarrelling factions depending on how intimate they were with Rand and how strictly they believed in the perfection of her thought; many more admirers drifted off into quietist non-participation in politics. (Increasingly, her old fogies form a kind of Old Right, a rearguard of True Believers.) Her philosophy and her novels, receding into history and not selling as well as formerly, continue to appeal in a less powerful though still lively way -- especially, as always, to the young.

The time, I think, cries out for reconsideration of Rand's ideas and person. It cries out for this powerful thinker and novelist seriously to be reconsidered by both detractors and worshippers.

Rand's following always had an elitist tinge, a superior-seeming aloofness, a reluctance to be tainted with outsiders and unwashed illogicals that made it a little cult-like.

But Rand was no Lafayette Ron Hubbard (1906-1984) or Joseph Smith (1805-1844), no founder of a new religion. (I will qualify this statement later.) Neither was she a dilettante. Although she said the chief purpose of her philosophical writing was to create the heroes she wished to write about as a novelist, I maintain she did not write her philosophy "on the side". Unusually for a non-academic, she was an important philosopher -- probably the 20th century's most important and profound non-academic philosopher. (Her true rank in the history of philosophy is probably higher than this suggests.) But Rand was not a pure philosopher. She did originally create her philosophy so that she could invent the kind of heroes she wished to write about in novels.

However, in her maturity Rand became so interested in philosophic thought that she hardly wrote fiction in her last twenty-five years.

Which, by the way, brings up a point.

In addition to being an important philosopher Rand was one of the 20th century's most serious and challenging novelists. Why do so few literary critics understand this? Can they be so blind and deaf? Is it because Rand pioneered so little in terms of literary form, inventing (as far as I know) no new literary techniques? Is it because of her tendentiousness? Is it because of the repulsive effect her ideas have on some critics of other philosophical schools? Surely her ideas and her novels are not understood by her critics as well as they imagine.

I believe Rand's novels, because of their many eccentricities (and "feminine" qualities -- notez bien, gender critics) are not appreciated as the compelling and thoughtful works they are. To dismiss The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged as mere heavy-handed, improbable, over-the-top Romanticism tricked out in sledgehammer prose is to miss the power of Rand's characterization, the intellectual power of her ideas, and the great effectiveness of her style. While no one would argue that John Galt's enemies in Atlas Shrugged would probably listen to his 50-page radio speech (I, for one, cannot believe this), one must not ignore the power and cohesiveness of that speech. While one is justified in thinking that a real-life Dominique Francon (in The Fountainhead) would not dedicate her life and body to destroying Howard Roark, the architect she loves, nor that he would persist in finding her admirable and remarkable (instead of pathetic), one cannot deny the power of the story as the author wrote it. Even the most jaded critic must acknowledge (as generations of American women have) the high voltage of the "rape" scene between Roark and Dominique in The Fountainhead. Is King Lear's surrender of his kingdom probable? Is The Fountainhead inferior to, say, Coriolanus? Is Atlas Shrugged seriously inferior to The Magic Mountain as a novel of ideas? I think not.

As a novelist, Rand is of high rank -- so high that the breathless improbabilities she serves up are mountains that she often leaps. As a philosopher, Rand's metaphysics, her approach to logic, and her epistemology in particular seem to me after thirty-five years' study to be challenging and thoughtful and deserving of debate. (Her An Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology seems to me likely one of the 20th century's most important philosophical works.)

But, very unfortunately, Rand had a doctrinaire personal style. Just as her opponents often dismissed and refused to debate her, she -- at least as often -- dismissed and refused to debate them. There was bitterness, misunderstanding, and contempt on both sides. Probably, for Rand, the issue at stake was her conserving her intellectual energy for her own writing; but, from the point of view of philosophy, the policy's results were at least unfortunate. Her policy of not debating opposing ideas meant that Rand was not taken seriously by many of the most serious thinkers and philosophers. Her positions which, properly publicized, might have transformed society decades ago, were delayed in coming to public attention and fruition until the 1990s (I discuss this later).

The essential problem seems to have been Rand's hypersensitivity to criticism. This compelled her to put on a manner which often came across as arrogance because, to a considerable extent, it was arrogant. Rand, I believe, suffered from a deficit of self-esteem caused by -- well, I don't know what it was caused by. For decades she waged a struggle for her ideas. She believed her struggle was against the weight of nearly all the philosophy of the past 2000 years. We must not be surprised that, with this belief, she became arrogant. (She might have profited from her former disciple Branden's self-esteem books and training courses.)

Whatever the reason for her seemingly arrogant confidence in her thought, Rand, I believe, though not as as logical as she believed, was by no means as negligible, barbaric, or irrelevant as her critics contend.

Her controversial, challenging, vehement stances concerning capitalism and altruism, and the doctrinaire flavor of her writings also contributed to her being viewed with obloquy by serious critics. (Does anyone remember that altruism was almost without serious intellectual challenge even in the late 1960s? That egoism was without cogent defenders?) It was often difficult in the 1960s to appreciate the seriousness and astonishing challenge of her work when, to many thinkers who read her only superficially, she appeared to be merely another conservative fanatic. (Yet, for her atheism, conservatives disliked her also.)

More important, it happens to be true that her philosophy and novels are flawed, perhaps deeply flawed. (I shall discuss this in a future essay.) So it was no wonder, on balance, that Rand was not appropriately appreciated.

Despite this, I assert that her work both as philosopher and novelist is of high quality.

Why is Rand, to make a second point, not only a great novelist but also a great philosopher?

Rand expounded a coherent philosophical system with closely argued positions in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, politics, and aesthetics: that is, in all the important divisions of philosophy. Her initial positions, once accepted, lead with apparent logic and certainty from one area of philosophy to the next, eventually creating an apparently logical densely-woven system. In a century, the 20th, where philosophy increasingly became humble, and eschewed the creation of systems, I believe this grand-scale system-building of Rand's was another reason that caused her to fail to be appreciated. But I am convinced that she will eventually be properly appreciated, and will emerge into greater prominence, and that her ideas will be viewed increasingly through sympathetic eyes.

In short, I think she will be seen in a few decades as one of the most important transformers, and probably for good, of the 20th and 21st centuries.

# # #

Rand called herself a rationalist. She described her philosophy as "Objectivism". (For the purposes of this essay I have assumed and shall assume a large amount of familiarity on the reader's part with Rand's philosophy.) This was because Rand held that existence just existed, that things are just "out there", existing independently of our consciousnesses. (She held, I think incorrectly, that most philosophers in the 20th century disputed this.) She held, therefore, that reason was the means whereby human beings could understand the world, and she had contempt for those who disagreed. (It is necessary to mention Rand's emotions because they were so woven into her philosophy's expression and her movement; Rand was no dispassionate thinker.)

Rand advocated egoism, and therefore capitalism, and therefore political nation-states limited to what she thought were the state's three proper functions: defence from enemies without, an objective system of justice and courts, and a police force to protect citizens from criminals. Rand thought she could prove the logic and necessity of this system, and that the efficacy of the system she advocated had been proved by the existence and history of the United States; despite all its faults (from her point of view), the United States most closely approached her ideal form of government.

In an Objectivist world with Objectivist nations, Rand believed, there would be no social welfare, no tariffs, no economic subsidies for anyone: each of these would be a violation of natural rights, the state's imposition of force -- state and taxation power -- on some for the benefit of others.

It was the postured ideality of Rand's Objectivist political system that caused the most important rupture in her movement. This was not the split in 1968 with her follower and "intellectual heir" Branden. It was the belief of some of her students and followers that her logical and ethical philosophy was inconsistent with its politics.

These followers believed that the logic of her philosophy, the egoistic logic of her ethics, required as its political expression not a limited constitutional democratic republic but laissez-faire anarchism. They formed the most lively part of the movement that succeeded strict Randism. They began to form the capitalist (big-L) Libertarian movement in 1971.

Rand had wanted her followers to remain what she called "students of Objectivism". She believed that before the state could be reduced to its proper role of defending what she called "man's [natural] rights", much educational work remained: the public would have to be persuaded of the logic and goodness of egoism and capitalism. The public would also have to be persuaded of the crucial importance of reason.

But the Libertarians believed that the time for political action was now. They formed the Libertarian Party of the United States to run political candidates immediately. They did not care whether any of the supporters of the Libertarian Party believed in man's rights, although they would have been happy if they did. Instead, the Party was to be a home for those who wanted to vote for less government and for immediate increased freedom from government.

Rand and her closest associates condemned the new movement in stinging words. They accused the new Libertarians of being irrational; of being without clear, logical principles; of being premature; and of being without intellectual foundations for their political action. The Libertarians, small-government minimalists and anarchists alike, ignored the rebuke.

Well, they didn't get very far. A few hundred thousand votes in each presidential election since then, and one electoral vote (!) in total. Whether the Libertarian movement has been worth the effort, I do not know.

But it has spread to many countries and, in a few, notably the Netherlands, has had an occasional substantial influence on those in or near power.

In the United States and Canada the Libertarian movement had a small but visible influence for about two decades. Though a minor political movement it seemed quite a lot more active and influential than the hard-line "Objectivists" and straight-line "Randists."

But more important than the Libertarian movement has been the continuing seeping into minds of Rand's ideas. As I discussed above, this has been substantial and additive.

We could discuss this forever. But I would like to conclude my burial of Ayn Rand with my own respectful requiem.

For no matter how atrociously Rand sometimes behaved, no matter how many errors she committed, she was one of the 20th century's most important people, the single person (perhaps after the physicist Albert Einstein (1879-1955) who seems most destined to affect all of the future.

# # # # #

Books about Ayn Rand and Objectivism

Home | About Grant | What's New | Links | Coming Soon | Send E-Mail

Last slightly modified: 10:18 AM 27/12/2003